My name is Abdulai Sankoh, I was born in a village called Babara Wallah, in the Lokomasama Chiefdom, Port Loko district in the northern region of Sierra Leone. I belonged to an extended family where typically there are a lot of children and many wives. In such a situation it is quite common for the individual to find him or herself with little or no educational background. At that time, as I was growing up, there was only one primary school in our village and no high school.

My name is Abdulai Sankoh, I was born in a village called Babara Wallah, in the Lokomasama Chiefdom, Port Loko district in the northern region of Sierra Leone. I belonged to an extended family where typically there are a lot of children and many wives. In such a situation it is quite common for the individual to find him or herself with little or no educational background. At that time, as I was growing up, there was only one primary school in our village and no high school.

Basically, after ones primary school, if you are not lucky enough, that will be the end of schooling. But I was fortunate. I was lucky to be helped by my friend’s uncle, who promised to take me with him to Freetown. He would provide my food and accommodation, but he was quite open and honest with me. “ I cannot do everything for you”, said my friend’s uncle, “especially sponsor your schooling.” But I was so pleased to have food and accommodation. Such a kind gesture. Nonetheless my junior secondary school was a tough experience, especially when it was a self-financed.

I was so happy that my mum had taught me how to make some chocolates, with a creamy milk. I used to take my chocolate to school and do some sales during lunch period. This was a very interesting enterprise as I had to sing my traditional songs and dance for my fellow pupils. I developed these marketing strategies to convince them to buy my chocolates. I set my savings aside for my school fees keeping them in an old scrap television which was my bank.

However, the beginning of tragedy struck me when my adopted uncle died, two years after I entered secondary school. At the age of thirteen it was still difficult to withstand the hard times alone. I had to ask for refuge at one of my neighbour’s compound and for permanent, not temporary, residence. My neighbour told me that I could stay but I would have to help with the domestic work and once more school fees would not be part of the agreement.

The Civil War started in 1991. It was to be known as a long brutal conflict where violence and atrocities were difficult to escape. In the year 1999, on January 6th when the rebels attacked Freetown, I was in the eastern part of Freetown, Calaba Town where I was staying at that time. This was the very community where rebels started to amputate the hands of the youths; the burning down of houses was the order of the day. Two of my senior house mates and I had to run outside, and hide in a public toilet for three days with no food and no water. Staying inside a house can cost your life from fire; trying to run might result in being hit by an a stray bullet; trying to stay in a public toilet might mean death by hunger and thirst. Life became very grim and very bleak.

God inspired me by cleverly showing me a vision of how to escape from that public toilet to a safe environment. The idea was to grab a dead dog lying there on the street; remove the dog’s skin and fur and attach the dog’s paw bone to my own hand to look as if one of my hands had already been cut off. Fortunately a broken bottle was lying close to the dog and enabled me to complete the gory procedure. Bingo, it worked! No sooner had I left the public toilet, just few meters away, I saw the first rebel group. By then I was putting on a good show of being very upset and in pain. They said to me, “Look at you, you are crying like a baby because your hand has been cut off.” I didn’t say a word, but I continued walking, going towards the west end of Freetown, which was safe and protected by international military troops. Eventually an ambulance saw me and took me away. The medic man wanted to give me some rehydration medicine, but I refused. I confessed to them that I was just pretending because I wanted to escape from the rebel zone. The medic man shouted for the ambulance to stop but fortunately I had my school ID. I showed it to them and they put me down in a safe place and told me I was a smart boy. I ended up at the National Stadium which was a displacement camp for thousands of victims. One of the house mates who hid with me in the toilet was shot as he tried to escape the other escaped successfully.

My passion for education continued to be my trigger in life as I continued my education and finally sat my senior high school external exams . My next level should had been going to university or a college, but again I was handicapped, because of my financial situation. I had to work in a factory for two years, and later I applied to study Travel and Tourism and Tourism Management at The Milton Margai College of Education, Brookfields Campus. It was so difficult for me to complete my studies, but I persevered. I tutored and helped the weaker students prepare their assignments in return for a fee.

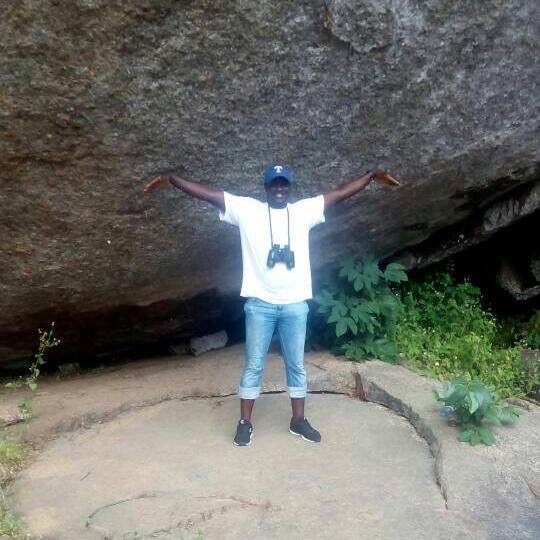

Since then I have been working as a tour guide at visit Sierra Leone [ VSL Travel]. I am not only a tour guide, but also an educational motivator helping communities who are less privileged and with inadequate educational materials. I was lucky to meet with Morag Keenan as my client on her visit to Sierra Leone as a tourist . I did not know she was also involved in education. After her observations she became concerned and discussed the situation with myself and her family and explored various options. Thus the Alec Russell Educational Trust was created. After further discussion with her family, lawyers and advisers I was formally invited to be the Sierra Leone Ambassador for ARET. I accepted the volountary position and currently supervise three projects. These are managing the education sponsorship of a village boy hopefully through to University; building a school at Joe Town in Waterloo for the children of the amputee victims in the Civil War and adults’ education initiative, called Adonkia Community Adults Educational Trust.

The Adonkia Community Adults Education Trust has thirty students benefiting from this charity. These adults had little or no opportunity to go to school. It has become a success around the peninsula, being the first and only facility available to those experiencing financial hardship. Many more wanted to attend but we have to work to a budget.

ARET is in its infancy as a charity and this type of support is realising the long-awaited dreams of the poor communities in Sierra Leone. We, who are involved in the work, are optimistic that this will make a positive impact in the social and economic development of Sierra Leone.